You misspelled POA. Which means of course you do something randomly different every time.I’m all for trying new techniques but I’m pretty by the book and usually just default to whatever the POH says.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Why bother with flaps on takeoff?

- Thread starter Salty

- Start date

luvflyin

Touchdown! Greaser!

This guy seemed pretty responsible. I doubt if he teaches things like that to primary students. It was just a rental checkout for me, I have a commercial certificateI’m all for trying new techniques but I’m pretty by the book and usually just default to whatever the POH says.

denverpilot

Tied Down

Go fly Vx without flaps and again with. Choose which is the better tool for rapid climbs. Cessna guys should try it at 30 and 40* flaps, too. Very educational.

Do that at our altitude and you’ll probably get to see how crashworthy the airframe is into the trees at the end of the runway.

Clark1961

Touchdown! Greaser!

- Joined

- Jun 7, 2008

- Messages

- 17,737

- Display Name

Display name:

Display name:

Where are there trees at the end of the runway out here?Do that at our altitude and you’ll probably get to see how crashworthy the airframe is into the trees at the end of the runway.

denverpilot

Tied Down

Where are there trees at the end of the runway out here?

LXV. North end.

Stewartb

Final Approach

Do that at our altitude and you’ll probably get to see how crashworthy the airframe is into the trees at the end of the runway.

Why’s that?

denverpilot

Tied Down

Why’s that?

Performance loss. Engine and airfoil. You won’t climb out of ground effect. Especially at 40.

You can simulate it there. Take the aircraft up to 6000’ and go into slow flight with flap 40 and see if you can power up and climb. Or get enough speed to retract the flaps and go back to cruise climb.

The colder out it is, the better your chances. But try it on a day when it’s at least 90F at the surface.

My runway is at 5885’. DA over 9000’ is common in summertime. Getting cooler out now, though. So our much better performance season is coming.

Clark1961

Touchdown! Greaser!

- Joined

- Jun 7, 2008

- Messages

- 17,737

- Display Name

Display name:

Display name:

Never have departed to the north there...LXV. North end.

denverpilot

Tied Down

Never have departed to the north there...

Wind was weird that day. That was also the day with the ancient CFI on board who pointed out the gap in the treeline to the left and said he was just pointing it out because he’d had to use it before...

He continued and said if you’re having that much trouble there on any particular day, a very shallow wide banked turn to the left until you’re headed south and then just wait until you get to Buena Vista to land... don’t bother trying to do a lap at LXV if it won’t climb. Just go downhill. Less banking.

Definitely.who do you think writes the PoH.....marketeers?

denverpilot

Tied Down

By the way, for @Stewartb - grab any POH and see if you can do the performance calculations from it for a departure from KLXV at 70F.

Doesn’t get that warm up there very often, but that north takeoff I am talking about above was done in those exact conditions.

Half tanks and two people in a 182. And we were climbing slowly enough that other CFI pointed out the gap in the trees.

Doesn’t get that warm up there very often, but that north takeoff I am talking about above was done in those exact conditions.

Half tanks and two people in a 182. And we were climbing slowly enough that other CFI pointed out the gap in the trees.

Eric Gleason

Pre-takeoff checklist

Procedures and speeds specified in the POH are often listed for reasons other than performance. Cessna's never going to tell you that you can reduce your takeoff roll if you save flap deployment towards the end because they're worried that increasing pilot workload will cause an accident, and that a jury will find it's their fault for making things too complicated for the pilot. But people who have tried it find that it does indeed result in a shorter takeoff in most aircraft.

Best glide speed is another one to be careful of. In most planes, the speed listed is not best L/D (furthest glide), and it's not minimum sink speed (longest time in the air). Both of those speeds will change with the weight of the airplane, and few manufacturers list different engine out glide speeds for different weights.

They're also not going to tell you that your longest glide can be accomplished by diving for ground effect and using the excess energy to stretch your glide where there's less induced drag, but it works quite well.

Best glide speed is another one to be careful of. In most planes, the speed listed is not best L/D (furthest glide), and it's not minimum sink speed (longest time in the air). Both of those speeds will change with the weight of the airplane, and few manufacturers list different engine out glide speeds for different weights.

They're also not going to tell you that your longest glide can be accomplished by diving for ground effect and using the excess energy to stretch your glide where there's less induced drag, but it works quite well.

Fearless Tower

Touchdown! Greaser!

You mean ‘modern Cessna’.Cessna's never going to tell you that you can reduce your takeoff roll if you save flap deployment towards the end because they're worried that increasing pilot workload will cause an accident, and that a jury will find it's their fault for making things too complicated for the pilot.

The short field takeoff technique described in the owner’s manual for the 1948 Cessna actually tells you to start the takeoff roll with zero flaps and as you approach takeoff speed, put the flaps full (Johnson bar).

And that’s in a tailwheel airplane.

Lachlan

En-Route

Procedures and speeds specified in the POH are often listed for reasons other than performance. Cessna's never going to tell you that you can reduce your takeoff roll if you save flap deployment towards the end because they're worried that increasing pilot workload will cause an accident, and that a jury will find it's their fault for making things too complicated for the pilot. But people who have tried it find that it does indeed result in a shorter takeoff in most aircraft.

Best glide speed is another one to be careful of. In most planes, the speed listed is not best L/D (furthest glide), and it's not minimum sink speed (longest time in the air). Both of those speeds will change with the weight of the airplane, and few manufacturers list different engine out glide speeds for different weights.

They're also not going to tell you that your longest glide can be accomplished by diving for ground effect and using the excess energy to stretch your glide where there's less induced drag, but it works quite well.

If you dive for ground effect around here, well, the ground effect you’re going to get is not gonna buff out. Unless you’re flying over a flat, relatively smooth surface, how in the world does your last sentence make sense? I’m imagining someone losing an engine at 3000’ agl and deciding to dive to ground effect. How steep of a dive? Should it be configured clean so that there’s a chance of exceeding Vne? What’s the proper technique for this so I can practice it next time I’m out? (I think there’s definitely a reason that, as you said, “(t)hey’re also not going to tell you that your longest glide can be accomplished by diving for ground effect...”)

Eric Gleason

Pre-takeoff checklist

You mean ‘modern Cessna’.

The short field takeoff technique described in the owner’s manual for the 1948 Cessna actually tells you to start the takeoff roll with zero flaps and as you approach takeoff speed, put the flaps full (Johnson bar).

And that’s in a tailwheel airplane.

That's interesting! Which model? I wonder if they did that for all models, even though the flaps in the 140 are far less effective than the bigger models.

The oldest Cessna manual I've seen was for the early era of electric flaps, mid-late 60s. It was around the time of Superbowl I, so I guess that makes it the "modern" era

I wonder if it's a procedure that was taken out when they changed to first style of electric flaps, where you have to turn the flaps off when they've moved as far as you want them to, rather than set-and-forget like the modern ones. Putting the flaps out late is quick and easy with the Johnson bar or with the newest ones, but not a good idea

Fearless Tower

Touchdown! Greaser!

Sorry I left it out. That was the 1948 Cessna 170. Flaps very small, and created a lot more lift than the drag of the later 170s.That's interesting! Which model? I wonder if they did that for all models, even though the flaps in the 140 are far less effective than the bigger models.

The oldest Cessna manual I've seen was for the early era of electric flaps, mid-late 60s. It was around the time of Superbowl I, so I guess that makes it the "modern" era

I wonder if it's a procedure that was taken out when they changed to first style of electric flaps, where you have to turn the flaps off when they've moved as far as you want them to, rather than set-and-forget like the modern ones. Putting the flaps out late is quick and easy with the Johnson bar or with the newest ones, but not a good idea

dell30rb

Final Approach

That makes me want to ask another question. I know this is a logically sound statement, but, if this is true, then why do you have to trim up for each notch of flaps in a mooney?

5 whole mph. woooo!

Definitely true, but again, with twice as much runway as needed, does that matter? Maybe getting off the ground asap is a good idea for other reasons...

how exactly?

Adding flaps increases the angle of attack at a given aircraft fuselage attitude (called angle of incidence), because the shape of the wing is changed. The angle of attack is the relationship of the chord of the wing to the relative wind as the wing goes through the air. The chord is defined as an imaginary line between the leading edge of the wing and the trailing edge. When you add flaps, you lower the trailing edge of the wing, changing the chord.

2 reasons for needing to add nose up trim in a Mooney. Adding flaps can move the center of pressure of the wing aft, changing the relationship to the aircraft's CG (making it feel nose heavy). Flaps can also disrupt airflow over the elevator. As we know the horizontal stab produces downforce. By blocking some of the airflow over the stab/elevator, a higher negative angle of attack is needed to produce the same downforce. Hence the need for more nose-up trim.

Eric Gleason

Pre-takeoff checklist

If you dive for ground effect around here, well, the ground effect you’re going to get is not gonna buff out. Unless you’re flying over a flat, relatively smooth surface, how in the world does your last sentence make sense? I’m imagining someone losing an engine at 3000’ agl and deciding to dive to ground effect. How steep of a dive? Should it be configured clean so that there’s a chance of exceeding Vne? What’s the proper technique for this so I can practice it next time I’m out? (I think there’s definitely a reason that, as you said, “(t)hey’re also not going to tell you that your longest glide can be accomplished by diving for ground effect...”)

It's a technique that many advanced glider pilots know quite well. My late uncle did it on his commercial glider checkride after losing some lift in the late afternoon, and he passed with flying colors.

I believe the technique is to dive at a relatively high speed, near Vne. And, yes, of course you'd be in a clean configuration. If the goal is to reduce drag with ground effect, why would you do it any other way?

My point was that the procedures in the POH don't necessarily reflect the best performance of the aircraft. They're a compromise between performance, pilot workload, company liability, and whatever other issues come up in the meetings where they discuss these things.

FormerHangie

En-Route

I guess it depends on the airplane. In a Cessna 120, I never bothered with flaps at any time.

I never bothered with them on my 170, either.

(That would be a Wills Wing Falcon 170, not a Cessna 170).

Tantalum

Final Approach

- Joined

- Feb 22, 2017

- Messages

- 9,250

- Display Name

Display name:

San_Diego_Pilot

Was this somewhere on short approach where he ducked down and made it to the strip? Or was he 10 miles from the field at 3K and he dove into ground effect and buzzed along fields? Genuinely curious. I also imagine winds and lift could be different lower down. My brother in law had a few outfield landings up in Canada and there are a lot of sailplane tricks they had up their sleeves that I'm not sure necessarily all translate to powered flight (wasn't Gimli glider and Hudson pilots glider pilots?)My late uncle did it on his commercial glider checkride after losing some lift in the late afternoon

Theoretically I get that ground effect gives you less drag, so getting into ground effect fast makes sense.. and maybe with a 50' wingspan the dynamics are different.. but I can't imagine cruising along in a Skyhawk somewhere over San Diego at 5K and then diving down to get into ground effect as a means of rescue

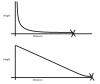

Chances are the drag dynamics are also different in a sailplane vs a conventional plane. For, say, a typical 172 I am picturing something like the graphs below. I could be wrong, but the drag at least feels like it goes way up with speed.. so while you're getting down into ground effect faster, you're ultimately just sacrificing more energy that you will not fully recover in ground effect

First curve is dive into ground effect, second is establish and fly best glide

Eric Gleason

Pre-takeoff checklist

I'm not sure what you mean by "drag dynamics," it's not a term I've heard before. This particular glider was a Schweizer 2-22, a ship that looks like it was designed with little regard to aerodynamics and only manages a 17:1 glide ratio. For comparison, something like a 172 is about 9:1.

He's not around to ask the specifics, but it was a technique the pilots in the club would use somewhat regularly. I think he learned it when he indulged in a week of high-performance glider flying in Colorado and was trying to earn his cross country distance badges. Off-field landings are not uncommon with gliders, so sometimes you're trying to get yourself into the best field to land in. In this situation, I think he was probably at about 1000' AGL a few miles from the airport.

This isn't one of those theory things that can only be duplicated in lab conditions; it's a pretty straightforward application of the science. Your total energy state is the combination of your kinetic energy (determined by your speed) and your potential energy (altitude). Assuming you keep your airspeed constant, your total energy is only affected by drag. So you get yourself into the region of substantially reduced drag quickly, and you get to keep that potential much longer.

He's not around to ask the specifics, but it was a technique the pilots in the club would use somewhat regularly. I think he learned it when he indulged in a week of high-performance glider flying in Colorado and was trying to earn his cross country distance badges. Off-field landings are not uncommon with gliders, so sometimes you're trying to get yourself into the best field to land in. In this situation, I think he was probably at about 1000' AGL a few miles from the airport.

This isn't one of those theory things that can only be duplicated in lab conditions; it's a pretty straightforward application of the science. Your total energy state is the combination of your kinetic energy (determined by your speed) and your potential energy (altitude). Assuming you keep your airspeed constant, your total energy is only affected by drag. So you get yourself into the region of substantially reduced drag quickly, and you get to keep that potential much longer.

denverpilot

Tied Down

There’s a few videos of glider folks stretching glides to runways by getting down into ground effect. It’s pretty impressive on the higher performance ships that are already over 30:1.

In power airplanes if you have a constant speed prop, pulling the prop all the way back is going to have a lot more impact. I practiced a power off 180 yesterday and pulled the prop all the way back... just to see how my airplane behaves. It added over 500’ to my touchdown aiming point.

If I ever had to do both (prop back and ground effect flight) I’ve screwed up really bad and I’m likely to take out a runway end identifier light or two.

Of course under controlled conditions aiming well down a nice long runway, the results of both can be eye opening for someone and give them a couple of tools in the bag for an “Oh ****!” day. Have to be real careful if a go around is needed too. Bringing the prop up will re-add the drag.

In power airplanes if you have a constant speed prop, pulling the prop all the way back is going to have a lot more impact. I practiced a power off 180 yesterday and pulled the prop all the way back... just to see how my airplane behaves. It added over 500’ to my touchdown aiming point.

If I ever had to do both (prop back and ground effect flight) I’ve screwed up really bad and I’m likely to take out a runway end identifier light or two.

Of course under controlled conditions aiming well down a nice long runway, the results of both can be eye opening for someone and give them a couple of tools in the bag for an “Oh ****!” day. Have to be real careful if a go around is needed too. Bringing the prop up will re-add the drag.

TK211X

Pre-takeoff checklist

I personally like to set one notch of flaps and retract after takeoff while passing a good altitude and speed. Usually that means passing 400 - 600 ft and 5-10 knots over my chosen VY or VX

Chip Sylverne

Final Approach

- Joined

- Jun 17, 2006

- Messages

- 6,008

- Display Name

Display name:

Quit with the negative waves, man.

You wanna leap off the runway in a hershey bar Cherokee? Full power, accelerate to 50 mph with slight back pressure. At 50mph, pull in two notches of flaps, count to 2, then pull back and hold Vx. Art Mattson developed this technique. Climbs like a homesick angel.

Tantalum

Final Approach

- Joined

- Feb 22, 2017

- Messages

- 9,250

- Display Name

Display name:

San_Diego_Pilot

I was taught that ground effect happens at about an altitude that is half of the aircraft's wingspan.. so in most GA planes that's around 10-15' off the runway.. which makes sense, as that's where you can feel the plane behave differentlygetting down into ground effect

So, are there glider pilots cruising along for miles at 20' off the ground? How do the dynamics work? Do they crank it up to Vne then dart over the landscape?

The drag profile of an aircraft is not constant, unless the airspeed stays constant (as you allude), so, honest question then:This isn't one of those theory things that can only be duplicated in lab conditions; it's a pretty straightforward application of the science. Your total energy state is the combination of your kinetic energy (determined by your speed) and your potential energy (altitude). Assuming you keep your airspeed constant, your total energy is only affected by drag. So you get yourself into the region of substantially reduced drag quickly, and you get to keep that potential much longer.

how do you keep your airspeed constant and yet quickly get yourself into a reduced drag environment, IE, ground effect? If you "dive" down to ground effect you'll naturally pick up airspeed, no? The reason I mentioned "drag dynamics" is because it is well know that total drag increases with parasitic drag as speed goes up. Yes, induced drag goes down, but at a lower rate, while parasite drag goes up at an increase rate. So if you "dive down" into ground effect you've dramatically increased your drag coefficient and sacrificed a ton of energy by doing so, and hence glide distance, just to get down to a lower altitude, IE, closer to terrain and obstructions, and have also reduced your glide range. The unknown to me is, how much does ground effect reduce your total drag? Perhaps it reduced a ton, and so the tradeoff is in your favor.. but this doesn't really pass the sniff test to me. Maybe glider dynamics are different.. but this sounds a little bit like the whole "getting up on step" thing with cruise speed, were people overshoot their altitude by 100' feet then dive down to get a bump in airspeed (not to open another Pandora's box though!)Assuming you keep your airspeed constant, your total energy is only affected by drag. So you get yourself into the region of substantially reduced drag quickly

denverpilot

Tied Down

So, are there glider pilots cruising along for miles at 20' off the ground? How do the dynamics work? Do they crank it up to Vne then dart over the landscape?

Nah the demos I’ve seen are all at normal approach speeds and no big dive or anything. Just calculated demos of it that they can make it with their hyper high glide ratios and the reduced drag.

Longest I’ve seen was about two miles.

denverpilot

Tied Down

Two miles! Man. I went up a few times but it's been years. Over due!

The video I saw was to a little glider strip in the middle of freakin' nowhere... just flat ground in the video going by and some sagebrush-y lookin' stuff...

You'd dunk yourself in the lake and/or crash into the trees at Boulder trying that... if you didn't hit a car on 119...

So, I totally forgot about this thread until today, when I realized something.

I continued to use flaps after this thread. Until.... after my engine overhaul my mechanic (also a very experienced pilot) convinced me to take off with no flaps because I wasn’t able to keep the cylinder head temps down as much as he wanted with flaps down.

So I’ve spent the last few months taking off with no flaps, until last week I did some experimentation and found it wasn’t effecting CHTs in any measurable amount.

I’m back to using flaps as prescribed in the POH. I did not like staying on the ground the extra 5-10mph it takes to get off without them. A lot of bouncing around that definitely felt less safe than getting off quicker. Also, the stall horn went off a lot more than I’d like if there was gusty wind, albeit with plenty of buffer still, and only very early before the effects of raising the gear could be attained.

I can see a definite difference, and after comparing both, much prefer a flaps takeoff in my mooney.

I continued to use flaps after this thread. Until.... after my engine overhaul my mechanic (also a very experienced pilot) convinced me to take off with no flaps because I wasn’t able to keep the cylinder head temps down as much as he wanted with flaps down.

So I’ve spent the last few months taking off with no flaps, until last week I did some experimentation and found it wasn’t effecting CHTs in any measurable amount.

I’m back to using flaps as prescribed in the POH. I did not like staying on the ground the extra 5-10mph it takes to get off without them. A lot of bouncing around that definitely felt less safe than getting off quicker. Also, the stall horn went off a lot more than I’d like if there was gusty wind, albeit with plenty of buffer still, and only very early before the effects of raising the gear could be attained.

I can see a definite difference, and after comparing both, much prefer a flaps takeoff in my mooney.

Hank S

En-Route

[QUOTE="Salty, post: 2657919, member: 29676

I’m back to using flaps as prescribed in the POH. I did not like staying on the ground the extra 5-10mph it takes to get off without them. A lot of bouncing around that definitely felt less safe than getting off quicker. Also, the stall horn went off a lot more than I’d like if there was gusty wind, albeit with plenty of buffer still, and only very early before the effects of raising the gear could be attained.

I can see a definite difference, and after comparing both, much prefer a flaps takeoff in my mooney.[/QUOTE]

Can you clarify this statement? I rotate at the same speed all the time, flaps or no, 70 mph. The book says 65-75, so I compromise and use 70. May go to 75 if the wind is gusty, or I'm heavy on a shorter field [with Takeoff flaps]. But the overwhelming majority of my takeoffs are Flaps Up. If I'm near gross, I may go to 75 mph, depending on how it feels and looks.

--first 7 years at obstructed 3000' field

--last 3 years on open-at-one-end/cliff-at-the-other 3200' field

--1½ years in between getting spoiled at wide open 5000' field with multiple approaches

I’m back to using flaps as prescribed in the POH. I did not like staying on the ground the extra 5-10mph it takes to get off without them. A lot of bouncing around that definitely felt less safe than getting off quicker. Also, the stall horn went off a lot more than I’d like if there was gusty wind, albeit with plenty of buffer still, and only very early before the effects of raising the gear could be attained.

I can see a definite difference, and after comparing both, much prefer a flaps takeoff in my mooney.[/QUOTE]

Can you clarify this statement? I rotate at the same speed all the time, flaps or no, 70 mph. The book says 65-75, so I compromise and use 70. May go to 75 if the wind is gusty, or I'm heavy on a shorter field [with Takeoff flaps]. But the overwhelming majority of my takeoffs are Flaps Up. If I'm near gross, I may go to 75 mph, depending on how it feels and looks.

--first 7 years at obstructed 3000' field

--last 3 years on open-at-one-end/cliff-at-the-other 3200' field

--1½ years in between getting spoiled at wide open 5000' field with multiple approaches

My plane stalls at 72 when clean. I’m not going to rotate at 70. Even at 75 I was getting stall horn every takeoff, so I settled on 80.I’m back to using flaps as prescribed in the POH. I did not like staying on the ground the extra 5-10mph it takes to get off without them. A lot of bouncing around that definitely felt less safe than getting off quicker. Also, the stall horn went off a lot more than I’d like if there was gusty wind, albeit with plenty of buffer still, and only very early before the effects of raising the gear could be attained.

I can see a definite difference, and after comparing both, much prefer a flaps takeoff in my mooney.

Can you clarify this statement? I rotate at the same speed all the time, flaps or no, 70 mph. The book says 65-75, so I compromise and use 70. May go to 75 if the wind is gusty, or I'm heavy on a shorter field [with Takeoff flaps]. But the overwhelming majority of my takeoffs are Flaps Up. If I'm near gross, I may go to 75 mph, depending on how it feels and looks.

--first 7 years at obstructed 3000' field

--last 3 years on open-at-one-end/cliff-at-the-other 3200' field

--1½ years in between getting spoiled at wide open 5000' field with multiple approaches

danhagan

En-Route

My plane stalls at 72 when clean. I’m not going to rotate at 70. Even at 75 I was getting stall horn every takeoff, so I settled on 80.

My previous Tiger stalled and rotated at 60mph with an 88mph Vx and 100 Vy. I don't hold aircraft on the ground trying to gain speed, I let the plane rotate when ready (which was always 60), and stayed in ground effect/leveled until near mid 80's then the climb.

I can only tell you my experience. I wasn’t comfortable with rotating earlier and having the stall horn blaring at me while still in ground effect.My previous Tiger stalled and rotated at 60mph with an 88mph Vx and 100 Vy. I don't hold aircraft on the ground trying to gain speed, I let the plane rotate when ready (which was always 60), and stayed in ground effect/leveled until near mid 80's then the climb.

danhagan

En-Route

I can only tell you my experience. I wasn’t comfortable with rotating earlier and having the stall horn blaring at me while still in ground effect.

Are you flying your own plane?

Most stall horns will be set for 5 knots over.

Stall horn can go off with a change in wind direction when you're not near stall.

Only had the "blaring at me" run one time leaving Carlsbad NM with 105* temp

PaulS

Touchdown! Greaser!

Cirrus calls for 50% flaps when taking off. My instructor when I first checked out in a Cirrus had me doing take offs by lifting the nose into climb attitude as soon as the airspeed came alive. So we were doing touch and goes, and decided to do a full stop taxi back to take off again. I took the active, full power, nose in climb attitude, and I think to myself, this airplane is rolling longer than it usually does, probably another 500 feet, but it finally lifted off, shot right up and past flap retraction speed. So I reach down to take out the flaps and realize I had forgotten to set them. He told me that he had noticed I didn't set the flaps but wanted me to see that by lifting the nose to climb attitude, the airplane lifts off when it is ready. That was on a long runway, I make sure the flaps are set when I take off, haven't missed it since.

Hank S

En-Route

My previous Tiger stalled and rotated at 60mph with an 88mph Vx and 100 Vy. I don't hold aircraft on the ground trying to gain speed, I let the plane rotate when ready (which was always 60), and stayed in ground effect/leveled until near mid 80's then the climb.

My Owners Manual says clean stall is 67 mph. I rotate at 70 mph, verify positive rate and raise the gear. By then I'm usually ~80, and I accelerate into climb pitch at Vx = 85mph until clear of whatever's beyond the runway, then drop the nose to Vy = 100mph - Altitude. Stall horn will chirp occasionally on climb (and final approach) when the wind is gusty.

Ted

The pilot formerly known as Twin Engine Ted

- Joined

- Oct 9, 2007

- Messages

- 30,006

- Display Name

Display name:

iFlyNothing

When I was flying the M20F I never tried a flaps up takeoff and always did the half flaps per the POH. But different planes are different. On the 310 and 414 putting in 10 degrees of flaps on a short runway would help get you off faster.

In the MU-2, flaps 5 and flaps 20 are both approved takeoff settings. Flaps 20 gets you off the ground noticeably sooner and I've been doing that for the past year, but on the last trip I tried flaps 5 takeoffs more to see what I think of it as I normally fly from longer runways. The benefit in a twin is less drag and more speed (i.e. more control) in the even of an engine failure right after takeoff. But there's also noticeably less lift. I need to experiment with it some more to see what I think I like best under what conditions.

In the MU-2, flaps 5 and flaps 20 are both approved takeoff settings. Flaps 20 gets you off the ground noticeably sooner and I've been doing that for the past year, but on the last trip I tried flaps 5 takeoffs more to see what I think of it as I normally fly from longer runways. The benefit in a twin is less drag and more speed (i.e. more control) in the even of an engine failure right after takeoff. But there's also noticeably less lift. I need to experiment with it some more to see what I think I like best under what conditions.

Checkout_my_Six

Touchdown! Greaser!

most GA aircraft....10 degrees of flaps produces more lift and lowers stall speed. That's enough for me.

sonopoa

Pre-takeoff checklist

- Joined

- Dec 28, 2018

- Messages

- 148

- Display Name

Display name:

sonopoa

The answer is look at the takeoff performance graphs in your POH. Configure the airframe for the runway and the temperature and manufacturers advice. The answer for a PA28 may be different to a PA34 may be different to a 747 may be different to a mooney on any particular day on any particular runway