You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Air Conditioning Effect Performance?

- Thread starter Garavar

- Start date

Well, you are going to be carrying extra weight so climb performance as well as useful load will be less than without. How much, I cannot say since I have never flown one but it makes sense.

Well, you are going to be carrying extra weight so climb performance as well as useful load will be less than without.

How significant?

I just edited my reply, I have never flown one so cannot say. I would recommend checking the POH.How significant?

Snowmass

Line Up and Wait

Air conditioning will require power but since temperature drops about 4.4 degrees F/1000 feet you shouldn't need it very long if you fly high. I live in extreme S.E. Arizona and have never felt any need for air conditioning in my plane but I cruise 9,500 to 13,500 feet.

Air conditioning will require power but since temperature drops about 4.4 degrees F/1000 feet you shouldn't need it very long if you fly high. I live in extreme S.E. Arizona and have never felt any need for air conditioning in my plane but I cruise 9,500 to 13,500 feet.

Adiabatic lapse rate is 2 degrees C or 3.5 degrees F per 1000 feet standard day.

PaulS

Touchdown! Greaser!

Yes, a knot or two cruise speed, a couple hundred feet in take off distance , decreased useful load and slightly less climb performance. This is for the Cirrus SR series. I imagine the 350 is the same. The take off distance, climb and cruise can be mitigated by turning it off. Useful load, not so much. But it's very nice to have when it's hot.

3393RP

En-Route

- Joined

- Oct 8, 2012

- Messages

- 4,219

- Display Name

Display name:

3393RP

A few summers ago I rode in a friend's air conditioned 172. It was 98° on the KTKI ramp, and the cold air blowing on me was most welcome. He flies alone on frequent business trips between McKinney, Houston, San Antonio, and Austin, so he wasn't concerned about weight and performance penalties when he decided to have it installed.

We were flying a short trip up to Ardmore, and stayed down pretty low, so I was able to enjoy the oddity of a Skyhawk with A/C for the entire trip, including takeoffs.

We were flying a short trip up to Ardmore, and stayed down pretty low, so I was able to enjoy the oddity of a Skyhawk with A/C for the entire trip, including takeoffs.

Yes, a knot or two cruise speed, a couple hundred feet in take off distance , decreased useful load and slightly less climb performance. This is for the Cirrus SR series. I imagine the 350 is the same. The take off distance, climb and cruise can be mitigated by turning it off. Useful load, not so much. But it's very nice to have when it's hot.

Any idea how much it would reduce useful load? Can't find numbers anywhere.

PaulS

Touchdown! Greaser!

Top of my head is about 75 pounds, not near a poh, I'll post again when I can look it up.Any idea how much it would reduce useful load? Can't find numbers anywhere.

Last edited:

pfarber

Line Up and Wait

- Joined

- Jun 20, 2021

- Messages

- 651

- Display Name

Display name:

pfarber

So the POHQUOTE="PaulS, post: 3247178, member: 2569"]Yes, a knot or two cruise speed, a couple hundred feet in take off distance , decreased useful load and slightly less climb performance. This is for the Cirrus SR series. I imagine the 350 is the same. The take off distance, climb and cruise can be mitigated by turning it off. Useful load, not so much. But it's very nice to have when it's hot.[/QUOTE]

So the POH allows for AC on takeoff? Pipers required it to be turned off... But thats a 360 vs a 5xx motor.

A car AC can take about a dozen or two hp... I can't see an airplane AC using less... Compressor still has to compress.

So the POH allows for AC on takeoff? Pipers required it to be turned off... But thats a 360 vs a 5xx motor.

A car AC can take about a dozen or two hp... I can't see an airplane AC using less... Compressor still has to compress.

Dan Thomas

Touchdown! Greaser!

- Joined

- Jun 16, 2008

- Messages

- 11,367

- Display Name

Display name:

Dan Thomas

Yup. It's not light. And it takes up some room for the evaporator in the cabin and the compressor on the engine. The compressor mounting has to be pretty stocky to withstand the vibrations it generates when compressing.Top of my head is about 75 pounds, not near a pot, I'll post again when I can look it up.

Useful load goes way down. All that cold air in the cabin weighs more

PaulS

Touchdown! Greaser!

Yes, a knot or two cruise speed, a couple hundred feet in take off distance , decreased useful load and slightly less climb performance. This is for the Cirrus SR series. I imagine the 350 is the same. The take off distance, climb and cruise can be mitigated by turning it off. Useful load, not so much. But it's very nice to have when it's hot.

So the POH allows for AC on takeoff? Pipers required it to be turned off... But thats a 360 vs a 5xx motor.

A car AC can take about a dozen or two hp... I can't see an airplane AC using less... Compressor still has to compress.

Yes, you are allowed to takeoff with it on, I do it all the time. I don't really notice it, but on a short rw I turn it off. The only prohibition is not to use the recirc function in the air. CO issue I believe.

PaulS

Touchdown! Greaser!

Top of my head is about 75 pounds, not near a poh, I'll post again when I can look it up.

It's on the Cirrus price list, 55 pounds

dfw11411

Pre-takeoff checklist

- Joined

- Oct 6, 2019

- Messages

- 136

- Display Name

Display name:

dfw11411

In South Texas AC is worthwhile on the ramp in hot months. Piper POH says to shut off AC when taking off and landing (for possible go arounds). My Cherokee 6XT has a sensor that automatically disables the AC when at full power. I switch it off once I enter the runway and it blows cool air for several minutes - usually long enough to get to altitude. On really hot days I may need it below 7,000, but usually it isn't needed once at cruise. Mine weighs 75 pounds. When on, the condenser drops down out of the belly and reduces IAS by about 4 knots.

kaiser

Pattern Altitude

- Joined

- Mar 6, 2019

- Messages

- 2,442

- Location

- Chicagoland

- Display Name

Display name:

The pilot formerly known as Cool Beard Guy

Not quite the Columbia - I flew an SR22 with similar power (IO-550 TN) with AC… airplane performed well… it’s still gobs of power. Probably more of a hit to useful load than actual performance. Either you haul AC parts, or you haul people/fuel/etc.

Pax love it so…

Pax love it so…

Dan Thomas

Touchdown! Greaser!

- Joined

- Jun 16, 2008

- Messages

- 11,367

- Display Name

Display name:

Dan Thomas

A car AC can take about a dozen or two hp... I can't see an airplane AC using less... Compressor still has to compress.

From https://www.aviationconsumer.com/industry-news/aftermarket-ac-new-lighter-options/

...we read:

These systems were developed for R-134a and are a bit lighter and more efficient than adapted R-12 technology. The STC systems are 16,500 BTUs, weigh 57 pounds and draw 100 amps. The field approval kit uses a 14,000-BTU system that weighs only 40 pounds and draws 75 amps. Both require 28-volt systems, 100-amp alternators and take 100 to 125 hours to install.

Newer Tech = Better Stats

The rookie in this field is Kelly Aerospace and their Thermocool system. This electrically-driven system was developed by Northcoast Technologies, which was purchased by Kelly. The compressor is a DC brushless system that only draws 33 amps (45 for a max cooling on a heat-soaked aircraft).

The system is rated for 14,000 BTUs and weights about 55 pounds. Neat features include a digital climate control and a switch outside the pilots door to turn the system on while connected to a GPU. They require a 100-amp alternator, or second alternator.

So a "dozen or two HP" is way off. The electrically-driven 14,000 BTU system draws 75 amps at 28 Volts. That's 2100 watts. At 746 watts per HP, that's 2.8 HP. Allowing for the alternator's and compressor motor's efficiency losses, it still wouldn't be more than 4 HP drawn off the engine. The engine-driven compressors would lose only the 2.8 HP.

Tantalum

Final Approach

- Joined

- Feb 22, 2017

- Messages

- 9,250

- Display Name

Display name:

San_Diego_Pilot

We have a Piper Archer in the club, a newer one with AC.. honestly I don't notice when it's on. It blows fantastically cold air and is a real life saver on the ground. The POH says to have it off for max performance for take off and landing. The Cirrus I was flying had one too, never noticed a performance difference with it on or off. The POH will give figures for changes in runway length and overall performance degradation. Personally, I didn't find the differences to be perceptible

Clip4

Touchdown! Greaser!

Looking at Columbia 350 or other high performance single. Wondering does AC affect the performance and/or useful load of aircraft?

Adds 55# to the BEW and the engine driven compressor uses about 6 hp.

Last edited:

Adiabatic lapse rate is 2 degrees C or 3.5 degrees F per 1000 feet standard day.

hmmm.... The dry adiabatic lapse rate is actually 3 degC (5.4 degF) per 1000 feet of rise and the moist adiabatic lapse rate is slower, around 1-2 degC per 1000 feet in rise. Of course, this is talking about how air cools as it (the air parcel itself) rises, like being blown up a mountainside.

Are you confusing this with the AVERAGE temperature lapse rate which refers to temperature conditions as YOU (vs. the air) go up?

Finer point, the 2 degC average temperature lapse is just that...an average. In actuality, it is not a rule. It could be a lot less and in cases of temperature inversions, go up.

Clip4

Touchdown! Greaser!

From https://www.aviationconsumer.com/industry-news/aftermarket-ac-new-lighter-options/

...we read:

These systems were developed for R-134a and are a bit lighter and more efficient than adapted R-12 technology. The STC systems are 16,500 BTUs, weigh 57 pounds and draw 100 amps. The field approval kit uses a 14,000-BTU system that weighs only 40 pounds and draws 75 amps. Both require 28-volt systems, 100-amp alternators and take 100 to 125 hours to install.

Newer Tech = Better Stats

The rookie in this field is Kelly Aerospace and their Thermocool system. This electrically-driven system was developed by Northcoast Technologies, which was purchased by Kelly. The compressor is a DC brushless system that only draws 33 amps (45 for a max cooling on a heat-soaked aircraft).

The system is rated for 14,000 BTUs and weights about 55 pounds. Neat features include a digital climate control and a switch outside the pilots door to turn the system on while connected to a GPU. They require a 100-amp alternator, or second alternator.

So a "dozen or two HP" is way off. The electrically-driven 14,000 BTU system draws 75 amps at 28 Volts. That's 2100 watts. At 746 watts per HP, that's 2.8 HP. Allowing for the alternator's and compressor motor's efficiency losses, it still wouldn't be more than 4 HP drawn off the engine. The engine-driven compressors would lose only the 2.8 HP.

The alternator drive has to withstand the added load and few p

planes are designed for this. There is already an AD for the mechanical drive for the IO550 and you are going to toss a lot of belts off the back of the IO520 with this set up.

Last edited:

- Joined

- May 18, 2007

- Messages

- 6,810

- Display Name

Display name:

jsstevens

I remember car AC systems were approximately 5hp load. So I’d guess the numbers quoted above at around 4 are close. Of course it affects performance-there’s no such thing as a free lunch. But can you fly precisely enough to use that 4hp if you need it to make a difference? I certainly doubt I can. And if I’m that close on performance and still planning to fly I’d better be fleeing an imminent tsunami or something equally dire.

John

John

Craig

Cleared for Takeoff

I flew a Warrior 2 that had a\c. When you hit the forward stop on the throttle, the compressor kicked off and the condenser retracted automatically. You had to back off the stop by a couple hundred rpms to get it back on.

RudyP

Cleared for Takeoff

The AC in the Mustang is pretty effective and I like that I can run it on the ground with GPU power or just the right engine turning. Means I can pre-cool the cabin before loading up the wife and kids on a hot day.

Timbeck2

Final Approach

The AC in the Mustang is pretty effective and I like that I can run it on the ground with GPU power or just the right engine turning. Means I can pre-cool the cabin before loading up the wife and kids on a hot day.

The air conditioner in my truck is pretty effective too.

RudyP

Cleared for Takeoff

The air conditioner in my truck is pretty effective too.

I bet it’s better. Plane AC always seems to be a little underperforming vs car/truck equivalents.

Dan Thomas

Touchdown! Greaser!

- Joined

- Jun 16, 2008

- Messages

- 11,367

- Display Name

Display name:

Dan Thomas

I maintained a P210 with the IO-520 and the Keith airconditioning system. It had the compressor mounted on the back of the engine, and a dual pulley on the engine's drive ran the alternator and the compressor. It never once threw any belt, nor did the drive suffer, but the heavy steel compressor mounting bracket cracked. We couldn't get another one, and had to decommission the system and remove the compressor until such time one could be found.The alternator drive has to withstand the added load and few p

planes are designed for this. There is already an AD for the mechanical drive for the IO550 and you are going to toss a lot of belts off the back of the IO520 with this set up.

If that drive can drive a 100-amp alternator for an electrically driven compressor, it can drive a compressor. The only issue might be the reciprocating load that a compressor puts on a drive, the same as the air compressor drives on the thousands of air compressors I rebuilt in an earlier career. The load on the drive during the compression stroke rises until the piston goes over the top, and then the residual air (or refrigerant) in the cylinder, the stuff that wasn't pushed out through the discharge check valve, pushes the piston down (until the pressure is gone and the intake opens), accelerating the crankshaft forward and loading any gears or splines in the opposite direction. That hammers at them, and as they wear and the clearances increase, they suffer even faster wear. A belt drive dampens a lot of that out. And the lash is worst at low RPM, like at idle. It disappears at operating RPM.

That drive pulley on the big Continentals? It's on the starter drive. And that starter starts the engine through those gears. They're really stout. The alternator or compressor load is miniscule compared to starting loads.

hmmm.... The dry adiabatic lapse rate is actually 3 degC (5.4 degF) per 1000 feet of rise and the moist adiabatic lapse rate is slower, around 1-2 degC per 1000 feet in rise. Of course, this is talking about how air cools as it (the air parcel itself) rises, like being blown up a mountainside.

Are you confusing this with the AVERAGE temperature lapse rate which refers to temperature conditions as YOU (vs. the air) go up?

Finer point, the 2 degC average temperature lapse is just that...an average. In actuality, it is not a rule. It could be a lot less and in cases of temperature inversions, go up.

When I’m flying I do use the average lapse rates to make decisions concerning possible icing, etc.

I’m also pedestrian enough to just use 3.14 to figure the area of a circle.

Dan Thomas

Touchdown! Greaser!

- Joined

- Jun 16, 2008

- Messages

- 11,367

- Display Name

Display name:

Dan Thomas

Yup. The dry adiabatic lapse rate needs dry air. No moisture at all. How many places on this planet fit that? Antarctica sometimes might come close, maybe.When I’m flying I do use the average lapse rates to make decisions concerning possible icing, etc.

I’m also pedestrian enough to just use 3.14 to figure the area of a circle.

The wet adiabatic lapse rate needs saturated air. Fog or cloud. IFR stuff.

Most of us are fine with 2°C per thousand feet.

PaulS

Touchdown! Greaser!

When I’m flying I do use the average lapse rates to make decisions concerning possible icing, etc.

I’m also pedestrian enough to just use 3.14 to figure the area of a circle.

That's a very bad way to determine where the freezing levels will be, going to bite you one day.

Dan Thomas

Touchdown! Greaser!

- Joined

- Jun 16, 2008

- Messages

- 11,367

- Display Name

Display name:

Dan Thomas

PaulS

Touchdown! Greaser!

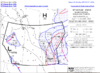

Huh. So what are charts like this for?

View attachment 106514

How many commercial or IFR pilots calculate their own freezing levels? How many airplanes don't have an OAT?

He didn't say he used those, he said he uses lapse rates.

Clip4

Touchdown! Greaser!

Che

I wasn’t addressing the factory AC. I was addressing putting a large amp draw on the alternator on a non-AC IO520, which I have experience with and it doesn’t work well.

When I’m flying I do use the average lapse rates to make decisions concerning possible icing, etc.

I’m also pedestrian enough to just use 3.14 to figure the area of a circle.

I wasn’t addressing the factory AC. I was addressing putting a large amp draw on the alternator on a non-AC IO520, which I have experience with and it doesn’t work well.

Dan Thomas

Touchdown! Greaser!

- Joined

- Jun 16, 2008

- Messages

- 11,367

- Display Name

Display name:

Dan Thomas

Whether one uses 1.5°C or 2.5°C, it will make a whole 5 degree difference in 5000 feet. The OAT gives one the rest. And if he uses lapse rates, the temp/dewpoint spread gives an idea of the moisture levels. At least he is thinking. That's more than we can say about people who encounter carb ice, unexpectedly, because they can't be bothered to check the metar for temp and dewpoint and a carb ice chart applicable to their airplane so that it isn't a surprise and they'll know exactly what it is when it shows up.He didn't say he used those, he said he uses lapse rates.

I encountered a lot of CPL/IFR students who still didn't understand the lapse rate thing. It's one of those things that's crucial. One should be checking the upper winds and temps forecast, looking at the temps for the various levels (6000', 9000', 12000', 18000', etc) and figuring the temp drop per thousand in those numbers. If it's more than 2°C, and the temp and dewpoint aren't far apart, watch out. Thunderstorms are a possibility, and thunderstorms eat airplanes. If the lapse rate is much more than 2°C, better stay on the ground unless the air is really dry. A factor of thunderstorm physics. Another factor is orographic or frontal lift.

I could never understand why pilots wouldn't be interested in the mechanics of such stuff. Chinooks, too. Fascinating. And morning fog development. Temp, dewpoint and surface moisture. Don't take off and get caught above a sudden ground fog.

Dan Thomas

Touchdown! Greaser!

- Joined

- Jun 16, 2008

- Messages

- 11,367

- Display Name

Display name:

Dan Thomas

If a 470 or 520 is throwing belts, it's usually the older shock-mounted alternator or generator. Vibration modes do it. One possible cure, if it's a three-bladed prop, is to reclock the prop 180°. Continental went away from that setup years ago but there are still plenty around, and I have also found a mishmash of shock-mount and non-shockmount parts on the same engine, and that leads to all sort of breakages and cracks and other hassles. Lots of junk flying around.I wasn’t addressing the factory AC. I was addressing putting a large amp draw on the alternator on a non-AC IO520, which I have experience with and it doesn’t work well.

That's a very bad way to determine where the freezing levels will be, going to bite you one day.

It’s worked to give me a ball park figure for over 45 years now, hasn’t bitten me yet. I’ve got 2 digital and one analog OAT readout in my plane, and of course, I use them inflight for the altitude I’m flying at.

It’s actually a great estimate, but I’d never bet my life on it.

I don’t fly with a meteorology textbook in my lap, nor am I a proponent of the (apparently quite prevalent) POA school of “measure it with a micrometer, mark it with a grease pencil, cut it with an axe.”

PaulS

Touchdown! Greaser!

Whether one uses 1.5°C or 2.5°C, it will make a whole 5 degree difference in 5000 feet. The OAT gives one the rest. And if he uses lapse rates, the temp/dewpoint spread gives an idea of the moisture levels. At least he is thinking. That's more than we can say about people who encounter carb ice, unexpectedly, because they can't be bothered to check the metar for temp and dewpoint and a carb ice chart applicable to their airplane so that it isn't a surprise and they'll know exactly what it is when it shows up.

I encountered a lot of CPL/IFR students who still didn't understand the lapse rate thing. It's one of those things that's crucial. One should be checking the upper winds and temps forecast, looking at the temps for the various levels (6000', 9000', 12000', 18000', etc) and figuring the temp drop per thousand in those numbers. If it's more than 2°C, and the temp and dewpoint aren't far apart, watch out. Thunderstorms are a possibility, and thunderstorms eat airplanes. If the lapse rate is much more than 2°C, better stay on the ground unless the air is really dry. A factor of thunderstorm physics. Another factor is orographic or frontal lift.

I could never understand why pilots wouldn't be interested in the mechanics of such stuff. Chinooks, too. Fascinating. And morning fog development. Temp, dewpoint and surface moisture. Don't take off and get caught above a sudden ground fog.

I used to do an off the cuff lapse rate calc to figure where icing levels start, but after watching, listening to @scottd Scott Dennstaedt I stopped doing that rather quickly. I took the poster's statement at face value, he is thinking, but he needs to expand his knowledge if he is playing near ice.

Your comment "it will make a whole 5 degree difference in 5000 feet" is accurate for your example, but I have two points, 5 degrees is huge for icing, is it 5 degrees colder or warmer than you expected at 5,000 feet? The second point is the difference could be a whole lot more than 5 degrees. On top of that, using OAT is too late, especially if you are distracted. It's like using a depth finder in a boat to avoid submerged rocks. It's certainly useful to help verify what you think will happen, but using OAT to verify your standard lapse rate calc from ground temps is just an all around bad idea.

On top of that, there are lots of very useful ice products out that give you a good wide area idea of where ice is. They are easy to use and give you a good idea of if you will run into problems. I start with airmets, then move to charts

On my last trip with and through ice the forecasts were pretty good.

The ice was contained in a layer I could fly over for most of my trip, with a quick descent through it to get to what were forecast and actually were vmc conditions. I used a combination of icing forecast product, ceiling products, forecasts, then I went along the route and looked at skew-t graphs, which backed up what I had seen in the forecasts. Next I looked for pireps, which pretty much were in line with what the forecast was. I took off from a VMC conditions, climbed to 7k, it was a bumpy climb (another concern with ice) I climbed to 9k to escape the bumps, which was fine for the 300nm leg. Along the way I asked controllers for ceiling and ice reports, which they were all to glad to give, one guy asked an airliner that had climbed about 10 miles ahead.

For the descent the controller asked me if I wanted to hang in the clouds, or wait. I told him I wanted the least amount of time possible in the clouds, but I had a passenger with sensitive ears, so I would be descending at 500 fpm. I asked him if there were any pireps, he told me a bonanza had just been in the clouds and reported trace to light. So my plan was still good. He cleared me to descend, PD, to below the clouds. I started down, turned on the TKS (fiki plane). I got in the clouds, the ice tabs on the wing were immediately iced, but all the tks covered surfaces stayed clean through the descent. I popped out a 4,400 feet and took a look at the wing tip, which is out of the tks stream. There was about a half inch of ice there. I called up the controller and told him it was moderate ice, definitely not trace or light.

Honestly I don't understand why pilots aren't more curious about this stuff either. I'm flying an ice capable airplane, but the info on how to use weather products is hard to come by. Scott has an excellent resource that accurately lays out the conditions for my entire route. Plus he explains how to use various tools in this talks and videos. On top of that he will do briefings with you on an instructional basis. His product seems to be successful, but there are hundreds of thousands of pilots in the US who would benefit from this stuff. I don't understand why his product isn't wildly successful. Pilots seem more interested in rules of thumb or quick review of how to do something rather than spending the necessary time to learn how to do it correctly. I still have a lot to learn, but I know rules of thumb can get me into bad situations. I don't use them any more.

It’s worked to give me a ball park figure for over 45 years now, hasn’t bitten me yet. I’ve got 2 digital and one analog OAT readout in my plane, and of course, I use them inflight for the altitude I’m flying at.

It’s actually a great estimate, but I’d never bet my life on it.

I don’t fly with a meteorology textbook in my lap, nor am I a proponent of the (apparently quite prevalent) POA school of “measure it with a micrometer, mark it with a grease pencil, cut it with an axe.”

I hope it continues to work for you.

Yup. The dry adiabatic lapse rate needs dry air. No moisture at all. How many places on this planet fit that? Antarctica sometimes might come close, maybe.

The wet adiabatic lapse rate needs saturated air. Fog or cloud. IFR stuff.

Most of us are fine with 2°C per thousand feet.

No. "Dry" means unsaturated. Not 100% dry. So, your comment, "No moisture at all", is not correct. Plus, the 2degC average temp lapse rate is NOT, read NOT, the same as the adiabatic lapse rate. Not at all. Adiabatic was brought up by orca64...for what reason, I don't know since he say he uses the average lapse rate instead.