OK. So tell me why these tachometers have yellow or red markings within their RPM limits?

View attachment 131854

View attachment 131826

The first is from a Piper Arrow. The PA-28 series had such tachs, depending on engine/propeller combinations. That prop would flex dangerously at certain resonant RPMs, hence the red band to stay out of. And that's a direct-drive engine.

The second is from a Cessna 152, which had the infamous gullwing prop on the O-235. A yellow band to avoid where possible.

There are many such aircraft; some direct-drive, and of course some geared. There is a lot of stuff in this business you just don't know.

Edit: One more, from the PA-28-180, from the TCDS for that airplane:

View attachment 131851

The Tach markings will reflect that, like so:

View attachment 131853

I flew one of those in 1973.

They'll act the same as a V-belt, which will allow slippage. But the cog-belt (timing-belt) drives common now do not absorb TV. That Subaru with the RAF redrive had such a belt, and TV was a serious issue in it. Those belts are nearly as rigid as steel, in tension.

Not true at all. Electrical failures are common in both cars and airplanes. But while an electrical failure in a car shuts down all the ignition and fuel injection, the airplane keeps running with its magnetos. Aircraft engines that quit do so for one of two reasons: (A) lack of maintenance, and (B) lack of pilot knowledge and skill. Running out of fuel, for instance, will stop any IC engine. Running the engine until the oil is all used up will do it too. Factors like this are NOT the aircraft manufacturer's fault.

There is a lot of math in any engine. As far a "magical math," are you referring to math you don't understand? The math involved in torsional vibration, for instance, is engineer-level stuff. Six years university stuff. It's not high-school math.

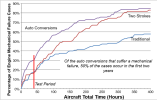

The wise man know this, here:

View attachment 131827

He also knows that both the green and red slices are really generous. The smartest of us know nearly nothing.