It's not a reduced airflow, but a pressure drop that leads to the temperature drop within the carb. The ice ends up collecting in the carb blocking airflow to the engine. The outside temperature can be 20°C or more. My big carb ice emergency was when the OAT was about 24°C.

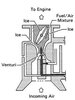

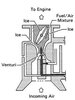

Closing the throttle restricts the airflow, alright, and it does that by making a much smaller area for the air to pass the throttle plate into the induction system. The air, in squeezing past that plate, accelerates a whole bunch, and if we listen to Bernoulli, as the speed of a fluid increases, its static pressure decreases, and then the Gas Laws show us that as pressure decreases, so does temperature.

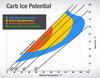

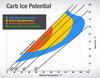

So the biggest temperature drop in a carburetor is not in the venturi. It's in the throttle plate/carb bore wall area, and that's why we get the carb icing charts looking like this:

Now, see and understand: the biggest risk of carb ice occurs at glide power, or throttle closed or nearly so. You can get ice at ambient temperatures up to 100°F that way, and serious ice up to 90°F, and in a very wide range of dewpoints. The cruise power ice risk is far smaller.

So closing the carb heat on final, especially when the temp and dewpoint aren't far apart, introduces a risk that you need to understand.

Now, that chart is pretty general. Different engines and airframe installations have different risk factors, with carbed Continentals being, generally, more ice-prone than Lycomings. But Lycs will still ice up, contrary to popular belief. I've had it several times in Lycs, and seen it on the ramp many other times. Students and instructors very often did not recognize it.

Another popular belief is that carb ice is a wintertime thing. False, absolutely false. That carburetor is an efficient little refrigerator, and makes ice the same way a freezer does: using a pressure drop.